Lending Club YTM Drift: Explained

04/12/2016

A copy of this write up is available here.

A copy of this write up is available here.

If you’ve seen this graph before, you know what I am talking about: the average returns for all Lending Club (“LC”) investors over time.

Embedded in this drift lower (yellow arrow) are two explanatory variables. The first being charge-offs and write downs from non-performing loans. The second, a rather important but ill-televised factor is the natural decay in returns due to Lending Club fees.

I think investors could become disillusioned with P2P products over time as these combined effects work together to erode returns, but it is worth realizing that at least part of the decay is inherent in the loan structure from Day 1. Remember: the initial Net Adjusted Return (“NAR”) or your own self-calculated IRR is the BEST you are going to do in fixed income investing. This isn’t equity investing. It’s fixed income investing!

Let’s consider how a fixed rate mortgage works. In the early years, most of the payment goes towards interest but as it amortizes proportionally more of the payment is devoted to principal repayment.

The same principle applies to LC loans, so the older the loan the more principal, and less interest, you receive. This means that LC fees become more pronounced over time as there is less interest to offset the fee drag.

While I’ve seen a few articles (available here) and blog posts (available here) which speak to the embedded Yield to Maturity (“YTM”) at different points along the amortization schedule I haven’t seen anyone explicitly define the decay you will see naturally over time.

I will do that here.

The first thing to mention is there are different decay factors for different loan maturities (36 or 60 month), which makes sense. 36 month loans will experience the drag to a greater extent than 60 month loans since the loans have an accelerated amortization schedule. In the graph below, I assume both loans have a 10% coupon issued at par meaning no premium or discount if you purchased on FolioFN and a 1% LC investor fee.

Since LC collects their fee on total payment, one would think that the interest rate impacts the decay factor (and it does), but only by a few basis points since the principal payment in a short tenure loan (3-5yrs) is the main determinant of the overall payment. For the sake of completeness, see this table for an example of a 10% and 20% coupon loan. The delta averages 5bps.

Embedded in this drift lower (yellow arrow) are two explanatory variables. The first being charge-offs and write downs from non-performing loans. The second, a rather important but ill-televised factor is the natural decay in returns due to Lending Club fees.

I think investors could become disillusioned with P2P products over time as these combined effects work together to erode returns, but it is worth realizing that at least part of the decay is inherent in the loan structure from Day 1. Remember: the initial Net Adjusted Return (“NAR”) or your own self-calculated IRR is the BEST you are going to do in fixed income investing. This isn’t equity investing. It’s fixed income investing!

Let’s consider how a fixed rate mortgage works. In the early years, most of the payment goes towards interest but as it amortizes proportionally more of the payment is devoted to principal repayment.

The same principle applies to LC loans, so the older the loan the more principal, and less interest, you receive. This means that LC fees become more pronounced over time as there is less interest to offset the fee drag.

While I’ve seen a few articles (available here) and blog posts (available here) which speak to the embedded Yield to Maturity (“YTM”) at different points along the amortization schedule I haven’t seen anyone explicitly define the decay you will see naturally over time.

I will do that here.

The first thing to mention is there are different decay factors for different loan maturities (36 or 60 month), which makes sense. 36 month loans will experience the drag to a greater extent than 60 month loans since the loans have an accelerated amortization schedule. In the graph below, I assume both loans have a 10% coupon issued at par meaning no premium or discount if you purchased on FolioFN and a 1% LC investor fee.

Since LC collects their fee on total payment, one would think that the interest rate impacts the decay factor (and it does), but only by a few basis points since the principal payment in a short tenure loan (3-5yrs) is the main determinant of the overall payment. For the sake of completeness, see this table for an example of a 10% and 20% coupon loan. The delta averages 5bps.

The first thing I will point out is the YTM (or IRR) starts out below the coupon. For a 36-month, 10% coupon loan, the YTM is 9.31%; in a 60-month 10% loan, the YTM is 9.57%. This is because of fees. If there weren’t any, the YTM would be equal to the coupon.

The decay in your YTM continues declining at an accelerating rate and by the loans’ half-life (month 18 and month 30) we see the expected YTM relative to the stated coupon is 8.76% and 9.21%, respectively!

So why does this matter? Two reasons: First, your IRR is going to be below the promised coupon and will only decline over time. This eventually results in a negative yield to investors in the last month of payment, which is virtually all principal.

Secondly, if you are trying to differentiate between this natural drift and your actual default experience you will need these decay factors to calculate a more accurate implied default rate. You can then use this to compare against Lending Club’s expected defaults. In principle, quantifying your ‘alpha’.

Here is a four step process to do that:

Keep in mind that if your portfolio is less than 12 months old, you probably have not experienced a full default cycle yet so comparing to Lending Club’s expected defaults will be apples and oranges. (Random Thoughts produced a good four part series discussing this: Part 1, 2, and 3 and 4 are available.

If your portfolio is 12-18 months old and your implied default is lower than Lending Club’s projections you’ve beaten the market!

The decay in your YTM continues declining at an accelerating rate and by the loans’ half-life (month 18 and month 30) we see the expected YTM relative to the stated coupon is 8.76% and 9.21%, respectively!

So why does this matter? Two reasons: First, your IRR is going to be below the promised coupon and will only decline over time. This eventually results in a negative yield to investors in the last month of payment, which is virtually all principal.

Secondly, if you are trying to differentiate between this natural drift and your actual default experience you will need these decay factors to calculate a more accurate implied default rate. You can then use this to compare against Lending Club’s expected defaults. In principle, quantifying your ‘alpha’.

Here is a four step process to do that:

- As I mentioned, if LC fees were zero your coupon would equal your portfolio IRR. Therefore, we can start with the weighted average coupon of your loan book. You can calculate it yourself or Lending Club provides this figure under Account>>Summary>> Click hyperlinked “More Details”.

- Calculate your portfolio’s IRR. I would recommend using the XIRR function and there are a variety of blog posts out there that describe this process. A link to one of them is available here.

- Using Table 1 in the Annex pull the decay factor for your 36M and 60M loan portfolio relative to the average age separately. For instance if the average age of your 36M loan portfolio is 12 months with a 10% coupon use -97bps. If your 60M portfolio is also 12 months old with a 10% coupon, use -52bps. Take the weighted average of these two figures (Suppose 60% of your total portfolio is 36M and 40% 60M paper then 60% x -97bps + 40% x -52bps).

- Subtract the sum of [your portfolio’s current IRR and the inverse of the decay factor] from the weighted average coupon.

Keep in mind that if your portfolio is less than 12 months old, you probably have not experienced a full default cycle yet so comparing to Lending Club’s expected defaults will be apples and oranges. (Random Thoughts produced a good four part series discussing this: Part 1, 2, and 3 and 4 are available.

If your portfolio is 12-18 months old and your implied default is lower than Lending Club’s projections you’ve beaten the market!

Learning to trade the structural illiquidity

09/09/2013

The global selloff we saw in June seems like a distant memory these days with most risk and rate products having reset to a new trading range. But markets are once again becoming lulled into a false sense of security. The plate tectonics are in motion once more; my seismograph is registering some early tremors. Investors beware.

But let’s first take a moment to understand the dynamics that were in play during the summer sell-off. It started with Bernanke’s speech on May 22nd where he suggested tapering was a near term probability. What happened next surprised even the most seasoned investors. At the epicenter was the treasury markets and from there rates and risk were simultaneously sold. Carry trades were unwound and greenbacks repatriated. The Fed was calling back its bountiful liquidity. That old saying still holds - “when the US sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold”.

The catalyst was the ‘shift’ in monetary policy but most believe the June sell off was big technical sell ticket with 1) traders front running the Fed 2) CTA’s getting caught in a ‘long squeeze’, 3) a modest amount of convexity hedging and 4) batting cleanup a tidal wave of redemptions from ETF and mutual funds. [For more information around the diminished role convexity hedging played in this sell-off please read this from creditwritedowns.com].

And while all these technicals played their hand, I think we've overlooked a pretty significant structural weakness that's been festering since the crisis. Over the last 5 years policy makers and regulators have sought to immunize the financial system from the events of 2008 which has meant smaller balance sheets for the nation’s biggest banks, punitive capital requirements, a separation of church and prop desk and a continued distrust of securitization. All this has meant significantly reduced capacity for markets to absorb sell orders with prime brokers reverting to their 19th century roots matching buy and sell orders like a bourse. Without market players with balance sheet capacity we should expect to see prices trade in jagged stairsteps during periods of market volatility. Prudence it seems has hallowed out what once was an impressive financial market torso.

So on one side the Fed has dulled volatility with excess liquidity and on the other regulators have added an enduring, structural component to it. We just didn’t realize it while the waters were rising. Now that the tide has gone out, we see we are all swimming naked. It’s ironic really.

Structural illiquidity is not a healthy sign in the markets, but it doesn’t mean we need to head for the hills. After all, imbalances are an opportunity in disguise. We simply have to deploy our capital with lighting speed (most of the carnage in June was contained to a two-week period). Today we are seeing dislocation in the muni market which has experienced massive redemptions after a lethal cocktail of longer [relative] duration, a steepening yield curve and the high profile default in Detroit. Act fast folks, these deals won’t last.

The global selloff we saw in June seems like a distant memory these days with most risk and rate products having reset to a new trading range. But markets are once again becoming lulled into a false sense of security. The plate tectonics are in motion once more; my seismograph is registering some early tremors. Investors beware.

But let’s first take a moment to understand the dynamics that were in play during the summer sell-off. It started with Bernanke’s speech on May 22nd where he suggested tapering was a near term probability. What happened next surprised even the most seasoned investors. At the epicenter was the treasury markets and from there rates and risk were simultaneously sold. Carry trades were unwound and greenbacks repatriated. The Fed was calling back its bountiful liquidity. That old saying still holds - “when the US sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold”.

The catalyst was the ‘shift’ in monetary policy but most believe the June sell off was big technical sell ticket with 1) traders front running the Fed 2) CTA’s getting caught in a ‘long squeeze’, 3) a modest amount of convexity hedging and 4) batting cleanup a tidal wave of redemptions from ETF and mutual funds. [For more information around the diminished role convexity hedging played in this sell-off please read this from creditwritedowns.com].

And while all these technicals played their hand, I think we've overlooked a pretty significant structural weakness that's been festering since the crisis. Over the last 5 years policy makers and regulators have sought to immunize the financial system from the events of 2008 which has meant smaller balance sheets for the nation’s biggest banks, punitive capital requirements, a separation of church and prop desk and a continued distrust of securitization. All this has meant significantly reduced capacity for markets to absorb sell orders with prime brokers reverting to their 19th century roots matching buy and sell orders like a bourse. Without market players with balance sheet capacity we should expect to see prices trade in jagged stairsteps during periods of market volatility. Prudence it seems has hallowed out what once was an impressive financial market torso.

So on one side the Fed has dulled volatility with excess liquidity and on the other regulators have added an enduring, structural component to it. We just didn’t realize it while the waters were rising. Now that the tide has gone out, we see we are all swimming naked. It’s ironic really.

Structural illiquidity is not a healthy sign in the markets, but it doesn’t mean we need to head for the hills. After all, imbalances are an opportunity in disguise. We simply have to deploy our capital with lighting speed (most of the carnage in June was contained to a two-week period). Today we are seeing dislocation in the muni market which has experienced massive redemptions after a lethal cocktail of longer [relative] duration, a steepening yield curve and the high profile default in Detroit. Act fast folks, these deals won’t last.

Gold's Selloff a Bad Omen for Equity Markets

05/22/2013

Dear Reader:

I'd first like to apologize for not updating this site more religiously, it certainly hasn't been for lack of material and content! Life just doesn't seem to budget for much down time. Nevertheless onto more pressing matters: I am at a point where I am starting to feel uncomfortable about owning equities and risk assets in general. I acknowledge there is very little alternatives but I believe the Fed will begin tapering their asset purchases in the next 6-12months. This will not bode well for the markets as the fundamentals don't support the multiples. A copy of my latest article, Gold's Selloff a Bad Omen for Equity Markets, is available on the CFAI website.

Dear Reader:

I'd first like to apologize for not updating this site more religiously, it certainly hasn't been for lack of material and content! Life just doesn't seem to budget for much down time. Nevertheless onto more pressing matters: I am at a point where I am starting to feel uncomfortable about owning equities and risk assets in general. I acknowledge there is very little alternatives but I believe the Fed will begin tapering their asset purchases in the next 6-12months. This will not bode well for the markets as the fundamentals don't support the multiples. A copy of my latest article, Gold's Selloff a Bad Omen for Equity Markets, is available on the CFAI website.

Looking Forward: Risks in the Year Ahead

01/24/2013

Dear Reader:

Looking Forward: Risks in the Year Ahead was written for the CFA Institute and a copy of this article is available on their website.

Dear Reader:

Looking Forward: Risks in the Year Ahead was written for the CFA Institute and a copy of this article is available on their website.

Pushing on a String

09/12/2012

Dear Reader:

Pushing on a String was written for the CFA Institute and a copy of this article is available on their website.

Dear Reader:

Pushing on a String was written for the CFA Institute and a copy of this article is available on their website.

The Dividend Yield Cliff

08/23/2012

The Dividend Yield Cliff was written for the CFA Institute and a copy of this article is available on their website.

Why Old People Still Matter

02/18/2012

A copy of this article in PDF format is available here.

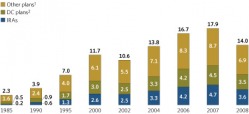

For decades, countries around the world have been able to ride their demographic trends toward higher GDP, yet these same favorable trends have started to crest and many will soon begin to experience them, not as convenient tailwinds, but rather formidable headwinds.

Current trajectories are calling for an aging and protracted global population that will put strain on our infrastructure, resources, and ultimately our capital markets. While not all economies are headed there at the same time, we will all inevitably “run a-ground”. And whilst today there exists a sizable gap between the BRIC economies (notably India and Brazil) and the G-7, eventually this arb goes away.

A copy of this article in PDF format is available here.

For decades, countries around the world have been able to ride their demographic trends toward higher GDP, yet these same favorable trends have started to crest and many will soon begin to experience them, not as convenient tailwinds, but rather formidable headwinds.

Current trajectories are calling for an aging and protracted global population that will put strain on our infrastructure, resources, and ultimately our capital markets. While not all economies are headed there at the same time, we will all inevitably “run a-ground”. And whilst today there exists a sizable gap between the BRIC economies (notably India and Brazil) and the G-7, eventually this arb goes away.

As asset allocators figuring out these structural trends will bear fruit. In equity markets for instance, growth is a quintessential piece of the valuation framework and an aging population is a huge drag on growth. The most immediate impact is on consumption: not only the absolute level but the industries in which they are spent. (Think quality of life industries like pharmaceuticals and personal care products).

Capital markets will be further impacted as an aging population will throw off the traditional balance between supply and demand. The argument is fairly simple but undeniably logical. If traditional portfolio theory holds we should retirees throttle back their risk exposure and shift demand from risky assets (like equity) to safe haven, income producing assets (like fixed income). This increasing demand for fixed income assets will put pressure on equities while supporting bond rates. In one hand we have a powerful retail trend paired with a strong bid from institutions under the captive capital doctrine so my question to you is: are low(er) interest rates here to stay? For me, the demand side arguments are simply too convincing to ignore.

An aging and protracted population also puts strain on our resources and the choice in how we divide up those resources. Today some 18.4% of our national income comes from government transfer payments with the lion’s share of that funding the retired and infirm. Are there better channels and uses of our funds? Say government funded research or infrastructure spending? Is this the stuff of capitalism..or self-directed nepotism?

When Social Security and Medicare were introduced we were neither old nor insolvent. Today we are coming under increasing pressure to meet our social and financial obligations so the hard choice about which promises we keep will have to be made.

What makes an aging and protracted population even more precarious is the fact that our topical solution is worse than the disease. In its most rudimentary form you battle an aging population by simply expanding the youth-base with favorably immigration and family formation policies. But longer term, this only exacerbates the problem, but allows the current generation to skip out on the hard choices.

What’s interesting to think about is the fact that history has never provided us a view into how capitalism fairs under an aging population. Capitalism has existed mostly in periods where there were favorable demographic trends (aka shorter life expectancies). The closest proxy we have is Japan, known as the widow maker for its graying population, ultra low interest rates and lackluster equity returns. Is this what we can expect from other graying economies?

What happens when the favorable trends we’ve been riding reverse and can no longer be counted on for incremental growth? Having defeated the likes of socialism and communism, capitalism has flourished and helped lift the standards and quality of lives around the world, but is its strength also its fundamental weakness? Moreover, is an aging population the logical conclusion of a successful capitalist model: will it be crushed under the weight of its own success?

What’s interesting to think about is the fact that history has never provided us a view into how capitalism fairs under an aging population. Capitalism has existed mostly in periods where there were favorable demographic trends (aka shorter life expectancies). The closest proxy we have is Japan, known as the widow maker for its graying population, ultra low interest rates and lackluster equity returns. Is this what we can expect from other graying economies?

What happens when the favorable trends we’ve been riding reverse and can no longer be counted on for incremental growth? Having defeated the likes of socialism and communism, capitalism has flourished and helped lift the standards and quality of lives around the world, but is its strength also its fundamental weakness? Moreover, is an aging population the logical conclusion of a successful capitalist model: will it be crushed under the weight of its own success?

_On China's Punch Bowl

1/13/2012

_ A copy of this article in PDF format is available here.

China’s New Year is January 23rd and this year will be the year of the dragon. How fitting. As much of the developed world is struggling to meet even sub-trend growth, China will itself enter a period of “slow growth” (consensus has it somewhere between 7.9% and 8.6%). Not bad by western standards.

Yet there is little doubt that the economy is sputtering: the housing bubble appears to have been pricked, exports are waning and internally the consumer is still too weak to pick up the baton. But the Chinese, unlike their western brethren, haven’t come to the end of their policy rope. Rates, reserve requirements, and Beijing’s coffers are all still comfortably unstretched. And there are large incentives for the Chinese to maintain their growth rates. A hard landing would exacerbate the already bubbling social unrest and destroy a good chunk of the newly minted wealth China has been able to create. Moreover, the CCP will want to insure a tranquil year as the Politburo is rechristened in late Oct/early November.

But this makes China a prisoner to its own growth story. In order to sustain growth the Chinese will have to continue supporting a lopsided growth model: one driven by expanding leverage and increased investment and infrastructure spending. And while in the short run, investment (and even a little overinvestment is 'ok') at some point the consumer and organic demand must become the driving force of an economy. Supply side economics in other words has a finite shelf life.

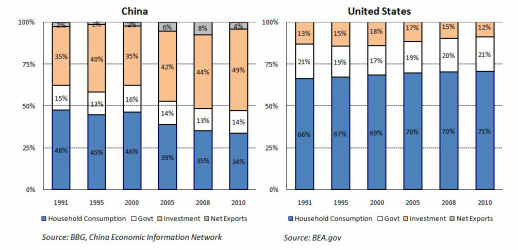

What's puzzling is the fact that China has always prided itself on having patient resolve. Creating a five year plan and sticking to it. And building a consumption driven economy has always been been something they've voiced support for. So why hasn't this been reflected in the hardnumbers? I will invariably get some slack for pointing to this tired graph on consumption vs. investment, but no one has adequately been able to explain why the long term trend for consumption is down.

China’s New Year is January 23rd and this year will be the year of the dragon. How fitting. As much of the developed world is struggling to meet even sub-trend growth, China will itself enter a period of “slow growth” (consensus has it somewhere between 7.9% and 8.6%). Not bad by western standards.

Yet there is little doubt that the economy is sputtering: the housing bubble appears to have been pricked, exports are waning and internally the consumer is still too weak to pick up the baton. But the Chinese, unlike their western brethren, haven’t come to the end of their policy rope. Rates, reserve requirements, and Beijing’s coffers are all still comfortably unstretched. And there are large incentives for the Chinese to maintain their growth rates. A hard landing would exacerbate the already bubbling social unrest and destroy a good chunk of the newly minted wealth China has been able to create. Moreover, the CCP will want to insure a tranquil year as the Politburo is rechristened in late Oct/early November.

But this makes China a prisoner to its own growth story. In order to sustain growth the Chinese will have to continue supporting a lopsided growth model: one driven by expanding leverage and increased investment and infrastructure spending. And while in the short run, investment (and even a little overinvestment is 'ok') at some point the consumer and organic demand must become the driving force of an economy. Supply side economics in other words has a finite shelf life.

What's puzzling is the fact that China has always prided itself on having patient resolve. Creating a five year plan and sticking to it. And building a consumption driven economy has always been been something they've voiced support for. So why hasn't this been reflected in the hardnumbers? I will invariably get some slack for pointing to this tired graph on consumption vs. investment, but no one has adequately been able to explain why the long term trend for consumption is down.

1

__ To me, this brings into focus a troubling, long term structural problem.

China's hand is being forced into investments for a few very simple reasons.

First, consumption based economies can usually only offer their patrons 3-4% of

real growth, far below China’s comfort level and the Street's expectation.

Second and perhaps most importantly, China is trying to build a society of

consumption off a tradition of saving. Historical savings rates for the Chinese

are very high and the proletariat would almost always prefer to save then to

spend. So in many respects the government is 'spending' for its constituents in

what can only be described as the longest running Keynesian experiment ever.

But in the end the government can only hope that one day the masses will turn

from net savers to net spenders. But as a strategist I work with so aptly put

it: “this isn’t Field of Dreams. He won’t come just because you build

it”.

Industry % of Fixed Asset Investment

Manufacturing 34.2

Real Estate 25.3

Transportation 8.7

Environment 8.1

Utilities 4.8

Other* 18.7

Cumulative YTD thru 11/30/2011. Source: NBS

*Other includes 14 smaller investment sectors to: Mining, Agriculture, Education, Hotels, etc.

Today, 13% of China’s overall GDP is property construction and if you add in upstream industries like concrete and steel the figure is closer to 20%. But even these figures ignore the ripple effects that will permeate through the economy. Many provincial governments rely on land sales and real estate taxes to generate revenue and banks have significant, albeit subordinate exposure to real estate. With the Chinese facing a weakened outlook and yet to-be-determined landing type, the PBC will have little choice but to continue feeding an insatiable beast built off increasing leverage, infrastructure spending, and speculative real estate.

China will hit a soft patch over the next two quarters, but I believe they have (and will take advantage of) sufficient policy rope to meet their full year 2012 growth targets. Yet over the long term that same rope will become a noose around their neck: China cannot continue to front run demand indefinitely. For that which cannot last, won't.

Industry % of Fixed Asset Investment

Manufacturing 34.2

Real Estate 25.3

Transportation 8.7

Environment 8.1

Utilities 4.8

Other* 18.7

Cumulative YTD thru 11/30/2011. Source: NBS

*Other includes 14 smaller investment sectors to: Mining, Agriculture, Education, Hotels, etc.

Today, 13% of China’s overall GDP is property construction and if you add in upstream industries like concrete and steel the figure is closer to 20%. But even these figures ignore the ripple effects that will permeate through the economy. Many provincial governments rely on land sales and real estate taxes to generate revenue and banks have significant, albeit subordinate exposure to real estate. With the Chinese facing a weakened outlook and yet to-be-determined landing type, the PBC will have little choice but to continue feeding an insatiable beast built off increasing leverage, infrastructure spending, and speculative real estate.

China will hit a soft patch over the next two quarters, but I believe they have (and will take advantage of) sufficient policy rope to meet their full year 2012 growth targets. Yet over the long term that same rope will become a noose around their neck: China cannot continue to front run demand indefinitely. For that which cannot last, won't.

_China: 20 Years on..

The Proof is in the lighting..

_

12/20/2011

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

I came across these photos of the Korean peninsula and African continent. Striking. Truly striking. I think there’s a case to be made that economic development can be measured one light bulb at a time.

Nothing new I can add here. I think the author says it best:

Development means many things. Health, education, roads. But at the end of the day, the most visible symbol of development is where there is light, and where there is not. When someone wants to show how communism retards development, they point to the famous image of the two Koreas: North Korea is dark, South Korea is bright. - Afrikent

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

I came across these photos of the Korean peninsula and African continent. Striking. Truly striking. I think there’s a case to be made that economic development can be measured one light bulb at a time.

Nothing new I can add here. I think the author says it best:

Development means many things. Health, education, roads. But at the end of the day, the most visible symbol of development is where there is light, and where there is not. When someone wants to show how communism retards development, they point to the famous image of the two Koreas: North Korea is dark, South Korea is bright. - Afrikent

Hear, Hear FOMC

11/22/2011

_

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

A copy of the FOMC meeting minutes are also available here.

The FOMC meeting minutes from early November were released today. First I’d like to applaud the Fed for not overstepping their monetary authority however tempting lower unemployment figures might be.

The Committee apparently weighed several additional monetary policies including setting explicit targets on unemployment, inflation, or nominal GDP. Now, I realize desperate times call for desperate measures, but setting targets unduly handicaps central banks and puts them in a precarious situation when things go awry. Central banks are then forced to choose between abandoning policy (and losing credibility) or carrying on even when it becomes counterproductive. The prime example of this is the ECB’s mandate on inflation. As long as inflation is above their comfort level, they hike rates. The last rate hike was as late as July 7th just as the sovereign debt crisis was beginning to bud. The ironic thing was inflation was only really a problem in Germany; the rest of the southern EUR countries were actually facing deflation.

You never want to underestimate the power of credibility and trust. Once you lose it it’s gone for a good, long while. The market believes the Fed’s commitment and more importantly their ability to effectively conduct monetary policy. For now, the collective balance sheet of Wall Street is happy front running CB policy, giving them monetary leverage, but what if we grow weary and stop believing Bernanke or Draghi?

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

A copy of the FOMC meeting minutes are also available here.

The FOMC meeting minutes from early November were released today. First I’d like to applaud the Fed for not overstepping their monetary authority however tempting lower unemployment figures might be.

The Committee apparently weighed several additional monetary policies including setting explicit targets on unemployment, inflation, or nominal GDP. Now, I realize desperate times call for desperate measures, but setting targets unduly handicaps central banks and puts them in a precarious situation when things go awry. Central banks are then forced to choose between abandoning policy (and losing credibility) or carrying on even when it becomes counterproductive. The prime example of this is the ECB’s mandate on inflation. As long as inflation is above their comfort level, they hike rates. The last rate hike was as late as July 7th just as the sovereign debt crisis was beginning to bud. The ironic thing was inflation was only really a problem in Germany; the rest of the southern EUR countries were actually facing deflation.

You never want to underestimate the power of credibility and trust. Once you lose it it’s gone for a good, long while. The market believes the Fed’s commitment and more importantly their ability to effectively conduct monetary policy. For now, the collective balance sheet of Wall Street is happy front running CB policy, giving them monetary leverage, but what if we grow weary and stop believing Bernanke or Draghi?

A One, Two Punch

_10/25/2011

First I’d like to apologize for missing my last entry; September was a busy month, but thankfully I found some time today.

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

So what can I say: I just cannot say enough about banks. In July I spoke about what additional regulation and capital requirements would mean for banks. Today, in the face of a seemingly imminent European meltdown, many are being asked to do precisely that.

But the equity markets are closed for new issuance so raising additional capital means taking down leverage and decreasing the amount of loans on their books. This of course exacerbates the problems in the real economy as struggling borrowers cannot refinance and new borrowers find there is less credit to go around. This is the situation in Europe.

For the US, banks are facing a whole new breed of problems. Operation Twist is a done deal. The Fed is increasing the average duration of its SOMA portfolio which has flattened the yield curve and impacted the outlook for banks in a very material way.

Coincidentally, and I’d say rather ironically, the Frank Dodd Act and Volker Rules have forced many banks back into traditional lending where interest margins are key. You see banks make money by borrowing short and lending long. The spread between their cost of funds and the yield on their loan book is their profit, their interest margin. When you play with the shape of the yield curve, you play with the banks' money.

I should probably also clarify what I mean by “cost of funds”. I use it rather loosely. It’s not just their borrowing costs (deposits, CD’s, LIBOR rates); it’s that plus their cost of doing business. When they make a loan, think about how many people they have to employ: a loan officer, an underwriter, a lawyer, and a whole team of Committees and analysts that make a loan book work.

But Operation Twist has effectively lowered what they are able to charge customers on the back end so they are now economically less incentivized to lend in the first place. The end result is the same in the US as it is in Europe albeit from a different catalyst.

The kicker to this story is the fact that banks now have to make a decision about where to put their money. What will produce the best return on their capital? Some now believe that is in the Treasury market. However paltry nominal yields might seem today, the cost of ‘doing business’ in the Treasury market is minimal: a couple of basis points at best. So when you compare the interest margins on originating a loan vs. buying a Treasury note, it might not be obvious which is going to return more in the long run. Throw into the pot, the added benefit of having to carry no capital against Treasury holdings and the asset class (at least to banks) starts to look very attractive even at these yields.

Yet the purpose of Operation Twist was to push investors out of Treasuries and not keep them in. I think academically Operation Twist was the right thing to do, but practically, exactly opposite. Combined with the refocus of many banks on 'traditional' bank operations and we have a perfect storm of legislative and monetary policy that puts a floor on Treasury prices and a cap on available credit. Its ironic to me as it seems the left hand does not know what the right is doing, but somehow the Fed and regulators were able to come up with a lethal Ali-style one, two punch!

First I’d like to apologize for missing my last entry; September was a busy month, but thankfully I found some time today.

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

So what can I say: I just cannot say enough about banks. In July I spoke about what additional regulation and capital requirements would mean for banks. Today, in the face of a seemingly imminent European meltdown, many are being asked to do precisely that.

But the equity markets are closed for new issuance so raising additional capital means taking down leverage and decreasing the amount of loans on their books. This of course exacerbates the problems in the real economy as struggling borrowers cannot refinance and new borrowers find there is less credit to go around. This is the situation in Europe.

For the US, banks are facing a whole new breed of problems. Operation Twist is a done deal. The Fed is increasing the average duration of its SOMA portfolio which has flattened the yield curve and impacted the outlook for banks in a very material way.

Coincidentally, and I’d say rather ironically, the Frank Dodd Act and Volker Rules have forced many banks back into traditional lending where interest margins are key. You see banks make money by borrowing short and lending long. The spread between their cost of funds and the yield on their loan book is their profit, their interest margin. When you play with the shape of the yield curve, you play with the banks' money.

I should probably also clarify what I mean by “cost of funds”. I use it rather loosely. It’s not just their borrowing costs (deposits, CD’s, LIBOR rates); it’s that plus their cost of doing business. When they make a loan, think about how many people they have to employ: a loan officer, an underwriter, a lawyer, and a whole team of Committees and analysts that make a loan book work.

But Operation Twist has effectively lowered what they are able to charge customers on the back end so they are now economically less incentivized to lend in the first place. The end result is the same in the US as it is in Europe albeit from a different catalyst.

The kicker to this story is the fact that banks now have to make a decision about where to put their money. What will produce the best return on their capital? Some now believe that is in the Treasury market. However paltry nominal yields might seem today, the cost of ‘doing business’ in the Treasury market is minimal: a couple of basis points at best. So when you compare the interest margins on originating a loan vs. buying a Treasury note, it might not be obvious which is going to return more in the long run. Throw into the pot, the added benefit of having to carry no capital against Treasury holdings and the asset class (at least to banks) starts to look very attractive even at these yields.

Yet the purpose of Operation Twist was to push investors out of Treasuries and not keep them in. I think academically Operation Twist was the right thing to do, but practically, exactly opposite. Combined with the refocus of many banks on 'traditional' bank operations and we have a perfect storm of legislative and monetary policy that puts a floor on Treasury prices and a cap on available credit. Its ironic to me as it seems the left hand does not know what the right is doing, but somehow the Fed and regulators were able to come up with a lethal Ali-style one, two punch!

Dot-com 2.0

8/14/2011

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

Looking at the data, we’ve only really just started to see a resurgence of IPO’s in the US. Yet the quality of the companies coming to market has me worried: the offerings seem opportunistic and laden with overly bullish assumptions.

The Street’s appetite for the likes of LinkedIn, Pandora, and the unofficial IPO of Facebook smacks of another dot com bubble as I am struck by just how many high profile social media companies have come to market with just the faintest hint of an earnings stream. Moreover, and as always true to form, Wall Street has embedded extremely bullish growth assumptions and called for multiples that are nothing short of absurd.

It’s true the dot com bubble is just shy of a decade old so I can appreciate the fact that the “lessons learned” might have faded just a bit. But what of MySpace? It wasn’t two months ago that MySpace was sold for a paltry $35M from an initial value of $580M in 2005. Have we learned nothing from our fallen brethren?

While researching this article I found some interesting facts about the MySpace deal I thought were less publicized so thought useful to put out here:

The NewsCorp/MySpace saga highlights the extreme fragility of internet valuations. Site usage and memberships are fickle and internet fades number in the hundreds. Yet social media derives a significant amount of its revenue from precisely this aspect of its business. They follow what I call the “Google model”. Provide the service a gratis and bank on memberships to bring in advertising revenue. But this makes companies heavily dependent on keeping usage up and memberships growing. Now, being the #1 search engine or networking site makes selling advertising slots easy but fall from the throne and you will almost certainly walk the path of MySpace.

The ‘print industry’ is all but extinct having tried to make this same model work. It’s not like this is anything new to us: we are all too familiar with its weaknesses so why are these ‘new’ companies any different? I think it’s important to note that I am not unilaterally opposed to the Google model: it is not inherently evil or a bad investment but at these multiples its ‘priced to perfection’. One hiccup and your value decrease precipitously.

Investing in the likes of Pandora or Groupon is like swinging for the fences: its venture capital not public capital. Valuations are based off future earnings that are projected from current member counts, not stable earnings and assets. I am not sure when this bubble will burst, but rest assured it will. Unfortunately, all we can do is wait and see, as a wise man once said: the markets can remain irrational far longer than you can remain solvent.

Looking at the data, we’ve only really just started to see a resurgence of IPO’s in the US. Yet the quality of the companies coming to market has me worried: the offerings seem opportunistic and laden with overly bullish assumptions.

The Street’s appetite for the likes of LinkedIn, Pandora, and the unofficial IPO of Facebook smacks of another dot com bubble as I am struck by just how many high profile social media companies have come to market with just the faintest hint of an earnings stream. Moreover, and as always true to form, Wall Street has embedded extremely bullish growth assumptions and called for multiples that are nothing short of absurd.

It’s true the dot com bubble is just shy of a decade old so I can appreciate the fact that the “lessons learned” might have faded just a bit. But what of MySpace? It wasn’t two months ago that MySpace was sold for a paltry $35M from an initial value of $580M in 2005. Have we learned nothing from our fallen brethren?

While researching this article I found some interesting facts about the MySpace deal I thought were less publicized so thought useful to put out here:

- First, MySpace now has 34.8M users which is about half of its membership base from the peak.

- In contrast Facebook now has 157.2M users.

- NewsCorp will maintain a minority stake in MySpace and Specific Media is offering NewsCorp a cash AND stock deal, implicitly suggesting that not even Specific Media thinks $35M is a good investment.

The NewsCorp/MySpace saga highlights the extreme fragility of internet valuations. Site usage and memberships are fickle and internet fades number in the hundreds. Yet social media derives a significant amount of its revenue from precisely this aspect of its business. They follow what I call the “Google model”. Provide the service a gratis and bank on memberships to bring in advertising revenue. But this makes companies heavily dependent on keeping usage up and memberships growing. Now, being the #1 search engine or networking site makes selling advertising slots easy but fall from the throne and you will almost certainly walk the path of MySpace.

The ‘print industry’ is all but extinct having tried to make this same model work. It’s not like this is anything new to us: we are all too familiar with its weaknesses so why are these ‘new’ companies any different? I think it’s important to note that I am not unilaterally opposed to the Google model: it is not inherently evil or a bad investment but at these multiples its ‘priced to perfection’. One hiccup and your value decrease precipitously.

Investing in the likes of Pandora or Groupon is like swinging for the fences: its venture capital not public capital. Valuations are based off future earnings that are projected from current member counts, not stable earnings and assets. I am not sure when this bubble will burst, but rest assured it will. Unfortunately, all we can do is wait and see, as a wise man once said: the markets can remain irrational far longer than you can remain solvent.

Zombie Banks

07/14/2011

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

The financial sector has lagged the broader market throughout most of the recession and well into the recovery. Logically, this makes sense given the fact that they’ve been at the center of nearly every major market calamity over the past four years. It seems as if banks have a proverbial hole in their balance sheet that they just can’t seem to fill. Quarter after quarter, we’ve seen write downs and bad press, and their stock prices have reflected this dismal outlook.

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

The financial sector has lagged the broader market throughout most of the recession and well into the recovery. Logically, this makes sense given the fact that they’ve been at the center of nearly every major market calamity over the past four years. It seems as if banks have a proverbial hole in their balance sheet that they just can’t seem to fill. Quarter after quarter, we’ve seen write downs and bad press, and their stock prices have reflected this dismal outlook.

Put the above chart in front of a contrarian and they might see ‘opportunity’: aren’t we due for a ‘correction’? After all, write off enough of a balance sheet and eventually you have a new one. But as much as I’ve tried to find the silver lining, I simply can’t.

Short term, banks are dealing with the European debacle where contagion concerns and short CDS contracts seem to weigh heavily on their outlook. As if this wasn’t enough, there are legacy loan books and continuing litigation claims that make valuing a bank’s assets and ultimate liabilities very difficult. When markets don’t know how to value an asset portfolio, they haircut it and move on. Better safe than sorry they’d say.

But what worries me the most are the longer term effects of increased public scrutiny and regulation. Already they’ve been forced to spin off their private investments, hedge funds, and their proprietary trading desks in the name of systemic risk. Layer onto this higher capital requirements, a subpar lending environment, and a mountain of new regulatory hurdles to overcome and I cannot help but wonder what ROE is going to look like going forward.

As regulation bears down on the banking sector I expect it to turn into a quasi-public institution, similar to a utility. A stable income base (bank deposits), heavy regulation, high entry barriers, and even lower leverage. For an industry predicated on levering up economic activity, the financial sector will be a shell of its former self (if regulators get their way).

That is not to say that bankers are incredible skillful at redeploying capital and finding innovative ways of making money and efficiently allocating capital. Already I have seen articles circulated that highlight the latest financial crazy: “commodity storage facilities”, principally metals storage. Instead of directly trading commodities, firms like Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and JPM have been buying up storage facilities to maintain some form of commodity beta.

The alpha drivers of yesterday are not the alpha drivers of tomorrow. Regulation will make certain of that. But when a regulator shuts one door, the bank always seems to find a window.

Short term, banks are dealing with the European debacle where contagion concerns and short CDS contracts seem to weigh heavily on their outlook. As if this wasn’t enough, there are legacy loan books and continuing litigation claims that make valuing a bank’s assets and ultimate liabilities very difficult. When markets don’t know how to value an asset portfolio, they haircut it and move on. Better safe than sorry they’d say.

But what worries me the most are the longer term effects of increased public scrutiny and regulation. Already they’ve been forced to spin off their private investments, hedge funds, and their proprietary trading desks in the name of systemic risk. Layer onto this higher capital requirements, a subpar lending environment, and a mountain of new regulatory hurdles to overcome and I cannot help but wonder what ROE is going to look like going forward.

As regulation bears down on the banking sector I expect it to turn into a quasi-public institution, similar to a utility. A stable income base (bank deposits), heavy regulation, high entry barriers, and even lower leverage. For an industry predicated on levering up economic activity, the financial sector will be a shell of its former self (if regulators get their way).

That is not to say that bankers are incredible skillful at redeploying capital and finding innovative ways of making money and efficiently allocating capital. Already I have seen articles circulated that highlight the latest financial crazy: “commodity storage facilities”, principally metals storage. Instead of directly trading commodities, firms like Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and JPM have been buying up storage facilities to maintain some form of commodity beta.

The alpha drivers of yesterday are not the alpha drivers of tomorrow. Regulation will make certain of that. But when a regulator shuts one door, the bank always seems to find a window.

The Silent Bid for Oil: Real Yields

06/13/2011

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

On July 7th 2008, oil peaked at $145.29. By December of that year (just 172 days later) oil hit a low just under $30 a barrel. Fast forward to 2011 and oil is back up and trading for over $100 a barrel. When you think about it, oil has had quite a remarkable journey.

Whilst its ascent is inspiring it is also quite unsettlin g. Deutsche bank estimates that for every 1cent ($0.01) increase in retail gasoline prices consumers spend approx. $1-1.5B less on non-energy consumption in the US. This inextricably links oil prices to the recovery and several prominent economists believe oil above $130 will materially destroy demand.

Naturally, the resurgence will also capture the attention of legislators in Washington, who are unable to come to terms with the fact that price is dictated by basic supply and demand dynamics. Before long we will have more hearings, more accusations and more calls for a windfall tax. Ironically or perhaps conveniently we gloss over the fact that contemporary monetary theory has created one of the biggest dislocations in the supply/demand equation, a problem that I will elaborate on momentarily.

Meeting trend growth (and keeping unemployment low), has become increasingly difficult. To stimulate the economy central bankers around the world have systematically lowered the level of interest rates over the last twenty years. (Low interest rates can weave that special kind of magic that takes 1% growth and makes it 3%).

As a politician or Reserve banker, it’s an easy sell, but for investors the policy decisions set by the central bank have a meaningful impact on the investment world. We’ve put our pension funds, insurance companies, and oil producing countries in a precarious situation: where do they park their capital when market yields are low and sometimes negative in real terms? PIMCO’s Bill Gross has, under great publicity, completely exited the US Treasury market for preciously this reason. A copy of his thesis is available here.

Yet unlike pension funds or insurance companies oil rich countries have the luxury of leaving their spare capacity in the ground. We must give them a compelling reason to monetize their oil reserves, and we simply haven’t. This has kept true capacity on the side lines which in turn forces oil prices upward. In essence oil producers are demanding a higher price to subsidize the low yields they will earn on their bond equivalent oil reserves.

Looking at the below chart you will notice real yields (Right hand side) have been trending downward while the price of oil (Left hand side) has steadily increased.

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

On July 7th 2008, oil peaked at $145.29. By December of that year (just 172 days later) oil hit a low just under $30 a barrel. Fast forward to 2011 and oil is back up and trading for over $100 a barrel. When you think about it, oil has had quite a remarkable journey.

Whilst its ascent is inspiring it is also quite unsettlin g. Deutsche bank estimates that for every 1cent ($0.01) increase in retail gasoline prices consumers spend approx. $1-1.5B less on non-energy consumption in the US. This inextricably links oil prices to the recovery and several prominent economists believe oil above $130 will materially destroy demand.

Naturally, the resurgence will also capture the attention of legislators in Washington, who are unable to come to terms with the fact that price is dictated by basic supply and demand dynamics. Before long we will have more hearings, more accusations and more calls for a windfall tax. Ironically or perhaps conveniently we gloss over the fact that contemporary monetary theory has created one of the biggest dislocations in the supply/demand equation, a problem that I will elaborate on momentarily.

Meeting trend growth (and keeping unemployment low), has become increasingly difficult. To stimulate the economy central bankers around the world have systematically lowered the level of interest rates over the last twenty years. (Low interest rates can weave that special kind of magic that takes 1% growth and makes it 3%).

As a politician or Reserve banker, it’s an easy sell, but for investors the policy decisions set by the central bank have a meaningful impact on the investment world. We’ve put our pension funds, insurance companies, and oil producing countries in a precarious situation: where do they park their capital when market yields are low and sometimes negative in real terms? PIMCO’s Bill Gross has, under great publicity, completely exited the US Treasury market for preciously this reason. A copy of his thesis is available here.

Yet unlike pension funds or insurance companies oil rich countries have the luxury of leaving their spare capacity in the ground. We must give them a compelling reason to monetize their oil reserves, and we simply haven’t. This has kept true capacity on the side lines which in turn forces oil prices upward. In essence oil producers are demanding a higher price to subsidize the low yields they will earn on their bond equivalent oil reserves.

Looking at the below chart you will notice real yields (Right hand side) have been trending downward while the price of oil (Left hand side) has steadily increased.

Many argue that low yields are a positive for growth, a high-octane shot in the arm sort of speak. Yet we walk a thin line between stimulating short term growth and over the long term destroying it. Especially today, the Fed is so focused on getting the economy back on track that they’ve ignored the indirect effects low yields have on oil. It seems as if we cannot have our cake and eat it too.

QE Effects

05/09/2011

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

Within the next month we will see the Fed’s second round of quantitative easing come to end. The question is what will happen then? How will markets react? The unwind of quantitative easing is historic as its rarely a tool wielded by central bankers in the first place. We’ve seen QE only once before…in Japan, but there are plenty of reasons why Japan shouldn’t be our model on QE. We are in ‘uncharted’ territory sort of speak.

Not only is QE to be unwound but rates need and must be raised. The tremendous rally in oil, agriculture and all things commodity-based is a function of demand, supply, and Bernanke & Co. It’s rumored that the FOMC will remove the words: “...for an extended period of time” from their communications. That means the time to make hay is quickly coming to a close.

But where will markets settle when the Fed starts to tighten its policy?

The important thing to remember is the Fed moves at a glacial pace and they do so not out of political deadlocks or inertia, they do so very intentionally. They want to give markets time to adjust so the tightening will likely come over several quarters as their balance sheet rolls off naturally.

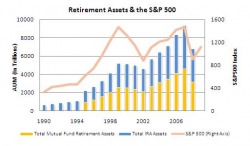

Nevertheless, the potential for a large market move is more than probable, it’s likely. Fortunately, we do have a brief data set to draw some conclusions from. If you think back to the period right after QE-1 ended and before the Fed had announced its second round of, we had a window into a world without monetary easing.

It was this period between March 31, 2010 and the Jackson Hole speech on August 27, 2010 where Bernanke hinted at additional ‘support’.

Above you will see several of the most important Fed announcements against a time series of the S&P 500, USD/EUR, and the 10Y Treasury rate.

You will notice something of an anomaly in the 10Y rate. Quantitative easing after all involves the printing of money, so you would expect that to depress interest rates, but it didn’t. In fact rates rose during the ‘money making’ period and fell shortly after it ended.

For this reason many questioned the effectiveness of QE. The best explanation I’ve heard on this anomaly postured that QE removed the specter of deflation and further economic downturn. If QE removed the chance of deflation, they theorized that rates below 2% was simply too low. Continuing on this thesis, the printing of money is inherently inflationary so why wouldn’t investors demand higher interest rates to compensate for the loss of real purchasing power?

For equity, the relationship between QE and stock prices is much more intuitive and well behaved. The markets rallied on news of QE1 & QE2. Hay was made as the cheap dollar became the currency of choice for carry trading putting additional pressure on an already weak dollar.

This had another indirect benefit for equity markets as globalization has transformed the income statements of many corporations. Today, nearly 50% of revenue for the S&P500 come from overseas sales which means that earnings become supercharged as they were translated back into a weaker USD. This naturally argued for higher equity prices even as you held the earnings multiplier constant.

But again the important area to focus on is the period between the end of QE-1 and the beginning of QE-2. During this period the Fed allowed their balance sheet to roll off effectively tightening the money supply. The S&P 500 lost close to 9% of its value and the dollar gained 5.8% against the EUR over this five month period.

In my mind, I have no doubt that a healthy amount of Fed dollars is sitting in equity markets, being used to own the likes of Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft, and double levered S&P ETF’s. But what happens when the Fed starts to call back those printed dollars? I’d say it manifests itself through weaker equity prices whether it’s driven by the unwind of carry trades or the reversal of favorable translation effects for non-USD earnings.

The only certainty we know is that quantitative easing moved markets, so a reasonable assumption would be that the end of QE will likely move them again. We have already seen treasury rates rallying and a softening in equity and EUR prices ahead of the end of QE. In light of the current situation in Europe, troubling housing data, and uncertainty surrounding QE 2.0, this would definitely be one of my ‘risk-off’ trades.

The Mother of All Debt Cliffs

4/16/2011

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

I remember hearing somewhere that if the government was run like a major corporation the CFO would be fired. I think now more than ever, most of you would agree with this statement. The national house is in disarray: unresolved deficits, an inflation-friendly monetary base, fast approaching debt ceilings, and hemorrhaging war costs come to mind first.

But as long as capital markets are open and willing to lend, the government hums along. Like a great many companies, the government must balance interest costs (which are real and reportable) with abstract and ‘out-in-the-tail’ risks like liquidity and rollover risk.

The battle is waged along the yield curve where the Treasury seeks to find bidders for its debt and like any good salesman widens its product offerings to capture many suitors.

The steepness of the yield curve dictates how expensive it is for the government to mitigate rollover risk by making it (relatively) more or less expensive to place long term debt. Today the steepness of the yield curve makes short term debt very compelling, but the government s behavior is more than just opportunistic. The US, since 1979, has been a chronic abuser of short term financing with average issuance in the 0-2Y space of 75%!

The best way to showcase what I mean is by looking at a debt maturity profile. It plots the amount of debt that is outstanding and coming due within the next few years. When debt comes in large blocks, people refer to it as a 'debt cliff'. Either you refinance the whole block at the same time or game over, you become insolvent.

Debt cliffs are most commonly seen in high yield issuers who have trouble securing long term financing and rely heavily on bank loans. But unlike high yield issuers, the US is creating a debt cliff by front loading the nation’s obligations on the short end, where yields are just 4bps.

I remember hearing somewhere that if the government was run like a major corporation the CFO would be fired. I think now more than ever, most of you would agree with this statement. The national house is in disarray: unresolved deficits, an inflation-friendly monetary base, fast approaching debt ceilings, and hemorrhaging war costs come to mind first.

But as long as capital markets are open and willing to lend, the government hums along. Like a great many companies, the government must balance interest costs (which are real and reportable) with abstract and ‘out-in-the-tail’ risks like liquidity and rollover risk.

The battle is waged along the yield curve where the Treasury seeks to find bidders for its debt and like any good salesman widens its product offerings to capture many suitors.

The steepness of the yield curve dictates how expensive it is for the government to mitigate rollover risk by making it (relatively) more or less expensive to place long term debt. Today the steepness of the yield curve makes short term debt very compelling, but the government s behavior is more than just opportunistic. The US, since 1979, has been a chronic abuser of short term financing with average issuance in the 0-2Y space of 75%!

The best way to showcase what I mean is by looking at a debt maturity profile. It plots the amount of debt that is outstanding and coming due within the next few years. When debt comes in large blocks, people refer to it as a 'debt cliff'. Either you refinance the whole block at the same time or game over, you become insolvent.

Debt cliffs are most commonly seen in high yield issuers who have trouble securing long term financing and rely heavily on bank loans. But unlike high yield issuers, the US is creating a debt cliff by front loading the nation’s obligations on the short end, where yields are just 4bps.

|

Source: Bloomberg, TreasuryDirect.gov

|

The above graph plots the US debt maturity profile against a composite of 6 blue chip companies in the US. You notice the cliff I was referring to? Over 37% of US debt (or $4.1T) is maturing this year while the blue chip average is 14%. The US is chronically exposing itself to rollover risk. Looking at it another way, the average maturity of US debt is just shy of 5Yrs (4.91Y) while the blue chip average is 6.25Yrs. This means the US is going to have to roll more debt over a shorter time period.

I know what you are may be thinking: treasury markets are some of the most liquid in the world, and more importantly, at present, dirt cheap. So why shouldn’t the DMO (Debt Management Office) issue short duration? 3M Treasury bills yield just 4bps while a ten year treasury yields close to 3.5%. That’s a yield spread of 3.46%, which is very rich. If you were a banker and I offer up a yield spread of 3.46%, you’d be picking up my dry cleaning and driving my kids to soccer practice.

I realize it’s a hard argument to make. Over the last 4 years, following the actual debt issuance of the UST over the more fiscally responsible blue chip average has netted the UST over half a trillion in interest savings. (See Appendix A in the PDF for a breakdown).

But these savings come at an implicit cost: it makes the US a defacto variable rate borrower, and one that is constantly rolling its debt into new money yields. The immediate risk isn’t the same for the US government as it is for a corporate issuer. The market will lend to the US, but one day markets are going to wake up and realize they are unpaid for their services.

Moreover, how do we wean a government off artificially low short term rates that are the equivalent of a teaser rate to a subprime borrower? Debt loads are close to 100% of revenue and deficits forecasted out as far as the eye can see.

I know what you are may be thinking: treasury markets are some of the most liquid in the world, and more importantly, at present, dirt cheap. So why shouldn’t the DMO (Debt Management Office) issue short duration? 3M Treasury bills yield just 4bps while a ten year treasury yields close to 3.5%. That’s a yield spread of 3.46%, which is very rich. If you were a banker and I offer up a yield spread of 3.46%, you’d be picking up my dry cleaning and driving my kids to soccer practice.

I realize it’s a hard argument to make. Over the last 4 years, following the actual debt issuance of the UST over the more fiscally responsible blue chip average has netted the UST over half a trillion in interest savings. (See Appendix A in the PDF for a breakdown).

But these savings come at an implicit cost: it makes the US a defacto variable rate borrower, and one that is constantly rolling its debt into new money yields. The immediate risk isn’t the same for the US government as it is for a corporate issuer. The market will lend to the US, but one day markets are going to wake up and realize they are unpaid for their services.

Moreover, how do we wean a government off artificially low short term rates that are the equivalent of a teaser rate to a subprime borrower? Debt loads are close to 100% of revenue and deficits forecasted out as far as the eye can see.

Countering Euphoria

12/28/2010

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

I am often pleasantly surprised by how eternally optimistic the human spirit can be. No matter how precarious a position we might find ourselves in, we tend to look for the good and discount the bad. Over the last few months economist after investment manager after Wall Street analyst have pointed to a tide of marginally better economic data as signs of a recovery. Whilst the numbers are ‘positive’ there are still plenty of negatives in the economy. Perhaps most important: pound for pound the scale still tips in favor of the bears.

Much of the upward revision in GDP has been predicated on the tax stimulus that was recently passed. I don’t doubt that a year from now we will be 3% wealthier but the growth is being subsidized with borrowed dollars which is preciously how we got into this situation in the first place. This time we are substituting the great mortgage machine for the Treasury press.

On either side of the political isle we have Democrats unwilling to cut spending and Republicans unwilling to raise taxes. What is our balance sheet going to look like at the end of 2011? Bond investors are already started voting with their feet. A recent treasury auction for 2Y notes went well but the 5Y auction didn't meet expectation. That tells me investors are comfortable with the credit worthiness of the US government for the next two years, but broaden that horizon to five years and their confidence wavers.

At its simplest we are transferring spending (and debt) from the consumer to the government. We are hoping to nurse the great American balance sheet back to health, but if the consumer doesn't get back on their feet soon we are going to have a second, much larger patient to take care of.

The other two 800lb, apparently translucent, gorillas in the room are housing and employment. Neither of which seem to be doing too well. Yes, jobless claims are at the lowest levels since 2008 but this is a sign that the jobs market is just being to thaw.

On to housing: many economists see housing headed for a double dip all by itself. The Case Schiller index for October showed the third straight month of decline; in fact only 4 cities (out of 20) posted home prices that were higher today than they were a year ago. This is particularly troubling since nearly a third of America's net worth is tied up in home prices. Nearly $6T as of Q3'10. The other $12T is tied to equity/401K accounts. To further my argument: a Moody's economist estimated that for every dollar decline in home equity, owners will spend ~5 cents less over the coming 18 months. With home prices set to take another dip, I don’t see how the American consumer will be ready to take the reins from the government and sooner or later the training wheels must come off.

With these sobering thoughts I leave you: Happy New Year!

I am often pleasantly surprised by how eternally optimistic the human spirit can be. No matter how precarious a position we might find ourselves in, we tend to look for the good and discount the bad. Over the last few months economist after investment manager after Wall Street analyst have pointed to a tide of marginally better economic data as signs of a recovery. Whilst the numbers are ‘positive’ there are still plenty of negatives in the economy. Perhaps most important: pound for pound the scale still tips in favor of the bears.

Much of the upward revision in GDP has been predicated on the tax stimulus that was recently passed. I don’t doubt that a year from now we will be 3% wealthier but the growth is being subsidized with borrowed dollars which is preciously how we got into this situation in the first place. This time we are substituting the great mortgage machine for the Treasury press.

On either side of the political isle we have Democrats unwilling to cut spending and Republicans unwilling to raise taxes. What is our balance sheet going to look like at the end of 2011? Bond investors are already started voting with their feet. A recent treasury auction for 2Y notes went well but the 5Y auction didn't meet expectation. That tells me investors are comfortable with the credit worthiness of the US government for the next two years, but broaden that horizon to five years and their confidence wavers.

At its simplest we are transferring spending (and debt) from the consumer to the government. We are hoping to nurse the great American balance sheet back to health, but if the consumer doesn't get back on their feet soon we are going to have a second, much larger patient to take care of.

The other two 800lb, apparently translucent, gorillas in the room are housing and employment. Neither of which seem to be doing too well. Yes, jobless claims are at the lowest levels since 2008 but this is a sign that the jobs market is just being to thaw.

On to housing: many economists see housing headed for a double dip all by itself. The Case Schiller index for October showed the third straight month of decline; in fact only 4 cities (out of 20) posted home prices that were higher today than they were a year ago. This is particularly troubling since nearly a third of America's net worth is tied up in home prices. Nearly $6T as of Q3'10. The other $12T is tied to equity/401K accounts. To further my argument: a Moody's economist estimated that for every dollar decline in home equity, owners will spend ~5 cents less over the coming 18 months. With home prices set to take another dip, I don’t see how the American consumer will be ready to take the reins from the government and sooner or later the training wheels must come off.

With these sobering thoughts I leave you: Happy New Year!

Liquidity Traps

_11/10/2010

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.

The topic today: QE2. As many of you know, last week the Fed announced plans to buy US Treasuries in the order of $600B over a 6-8 month window. And whilst it was expected, there has been a healthy dose of debate over the program's effectiveness and long run implications. Personally I am very worried about QE2. I am mostly troubled by the Fed's inability to stimulate demand. I hear the term "liquidity traps" mentioned more and more these days. It's essentially what happened to Japan in the early 90's and it’s a central banker's worst nightmare. It means that the central bank has lost control of it monetary policy: no matter how low interest rates go or how much liquidity is pumped into the system, it fails to stimulate demand for loans and commerce. This is true because the Fed can not directly affect employment or growth levels simply by lowering rates or making cash available to the economy. There has to be an underlying need or demand from the market. Without the demand to capitalize on these favorable investment conditions, the Fed becomes powerless in their abilities to change the projectory and momentum of the economy. The Fed starts 'pushing on a string'.

Since the end of 2008, the Fed has dropped rates to near zero percent. As the recession deepened and capital markets seized up, the Fed turned to outright quantitative easing and pumped additional currency into the system. All told over $1.7T. This first injection of capital was meant to stabilize the banking system and compensate for the fact that the velocity of money had fallen off a cliff. A number of central banks employed similar strategies and I think there is general consensus that these actions pulled us back from the brink.

A copy of this article is available in PDF format here.